Encouraging the Scientist in Your Preschooler

If you follow the discussions about education reform and improvement, you will have heard much about the deplorable performance of U.S. students in the STEM fields—Science, Technology, Engineering & Math—at the high school and college level. Effort to improve this performance usually centers on tougher standards and more testing, often for middle school and up.

We think that’s the wrong approach. The scientist in each child is born (or not born) in preschool.

In a Montessori classroom, the Sensorial Exercises are designed to foster an interest in the natural world. Here, during the formative years of their lives, children develop many key attributes of the successful scientist:

- Observing carefully, with all senses. In contrast to computer screens, which are two-dimensional and primarily visual, the sensorial activities heighten observation skills by training all of a child’s senses. Children listen to differences in sound made by shaking cylinders to match, or tones in the scale made by the Montessori Musical Bells. Blindfolded, they match wooden tablets by their weight; other tablets by their heat conductivity or roughness of texture. They match taste and smell bottles; they arrange rods by lengths and cubes by volume. They put together complex, three-dimensional puzzles by using multiple sense modalities in conjunction. Why does this matter? In addition to the fact that many professions, from cooks to research scientists, need finely-tuned senses, deliberate, sequenced observational training helps children become active observers of their environment. And of course, the world is a much more enjoyable place when we have the tools to notice and appreciate the beauty around us!

- Categorizing things by their attributes. One of the key skills possessed by a scientific mind is the ability to ascertain similarities and differences, and to group things accordingly. In the Sensorial area of the Montessori preschool classroom, children learn precisely this skill. They identify attributes—length, width, height, color in wide gradations, taste, texture and so on. They acquire the vocabulary to accurately capture and describe what they see (mauve, magenta, crimson—instead of just "reddish"). They learn to sort and arrange things by their characteristics.

- Developing a scientific vocabulary. Dr. Montessori observed that preschool-age children operate with an "absorbent mind", that is, they can learn big words in an effortless way, just by being exposed to them:

We have to conclude that scientific words are best taught to children between the ages of three and six; not in a mechanical way, of course, but in conjunction with the objects concerned, or in the course of their explorations, so that their vocabulary keeps pace with their experiences. For example, we show the actual parts of a leaf or flower, or point out the geographical units (cape, bay, island, etc.), on the globe. (The Absorbent Mind, p. 175)

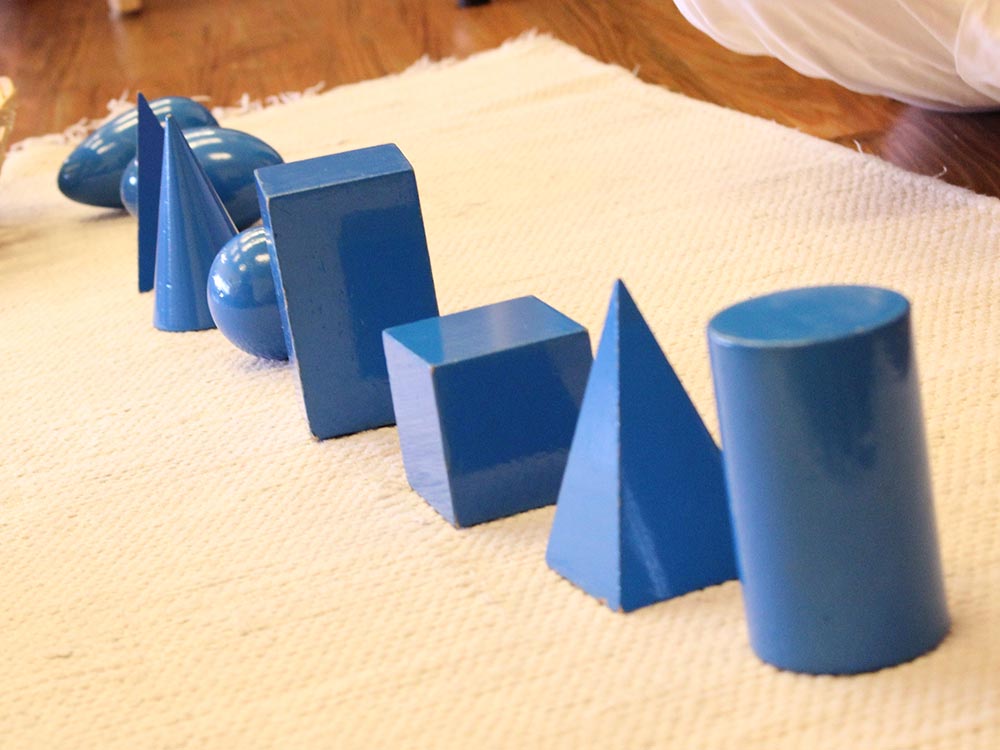

As part of the sensorial exercises, we expose children to a range of scientific vocabulary: they are introduced to the names of different forms of leafs (palmate, acicular) as they trace and match them; they identify land and water forms (peninsula, archipelago) as they work with water and clay to make these features in miniature; they make maps of the world, and learn the names of countries and states; they learn the names of two-dimensional geometric shapes and three-dimensional geometric solids (triangular pyramid, rectangular prism). The primary value here is not even the specific terms that the child retains, but the fact that she develops an inner norm for what it feels like to use vocabulary to heighten and capture one’s observations. Language itself becomes a precision tool to classify and categorize the world one perceives, rather than just a series of vague impressions.

The preschool-aged child, given his proclivity for observation and retention, is naturally inclined to develop a passion for science. So whether your child attends a Montessori school or not, there’s a lot you can do at that age to support your child’s budding scientist within:

- Spend at least half a day outside, exploring nature, on as many weekends as you can. In California, we are blessed with amazing nature, and a warm climate that enables us to be outside year-round. By taking your child out to explore the great outdoors, you naturally foster her interest in scientific inquiry. Whether she’s a toddler going on a short walk in a local park, picking up pine cones, rocks and flowers, or a five-year-old exploring the tide pools, unhurried outdoor experiences with you as a companion, engender an underlying fascination with the observable, natural world. The goal is not to make these instructional events: you’re not there to teach her about science so much as to let her use all her senses, let her explore at her pace, let her become enamored with the world around her, and curious about what makes it work. For ten fun things to do outdoors in OC, click here; this blog about OC parks is also full of great ideas; I refer to it often when I visit OC with my children.

- Express enthusiasm for technology as well as nature. While it’s particularly important to explore nature, we sometimes forget that for our children, everything is new and unfamiliar, whether natural or man-made. If your toddler is drawn to the garbage truck every time it passes, or really likes the shininess of a railing’s metallic surface, or notices every time an airplane passes overhead, treat these moments as instances of scientific exploration. An early fascination with technological innovation is a common characteristic of great scientists.

- Point out and name what you observe in the world about you. Just like we give children words in the classroom—for leaf shapes, for rocks, for land and water forms—you can provide much vocabulary in response to your child’s gaze and interests. Don’t worry if you don’t know all the scientific terms yourself: often, it’s helpful to just describe what you see—the bright red color of a maple leaf in autumn; the warmth of the sun on your skin; the fact that the sand is wet on the beach where the high tide covered it. If you can, and if your child is interested, do provide short explanations, of course—and use questions you can’t answer as a jumping-off point for joint research at home!

- Ask and answer questions about how things work. Recently, I was getting ready to go out to a park with my six-year-old daughter, when she, out of the blue, hit me with this series of questions: "Mama, there are some things in life that I don’t quite understand. Why does the light turn on up on the ceiling, when I flick the switch in the wall? Were there always bananas—and if not, where did they come from? What pushes the water up in a straw when I drink? How come the water in the toilet stops by itself after I flush?" Welcome questions like this—and do your best to answer them. We took off the top of the toilet tank, and watched what happened. I didn’t know the vocabulary for all the parts either—but you can always look it up! "Let’s find out together" are great words to use often!

- Include good, well-illustrated non-fiction books in your home library, and re-read them often. Picture books are a great way to introduce the fascinating world around us to young children. You can create many tie-ins to your excursions, for example, reading about constellations or moon phases as you spend time outside on a winter evening, or about marine creatures before you visit tide pools. Books are also a great way to bring new vocabulary terms to life: make reading interactive, as you name the things you see on the pages, and, on the second or third read, ask your child to find animals or plants or tools on the pages. Click here for a convenient Amazon list of some of our favorite non-fiction picture books for ages three to nine.

The preschool years are a wonderful time for making shared memories with your child. Going out into the world together, slowing down, noticing the sights, smells, sounds around us are wonderful ways to enrich your child’s preschool education—and to enjoy these precious years, when your child is so immensely curious, so aware and still so excited to be together with you.